Field Notes

Written By:

Jennifer McMaster

Photos By:

Jonathon Donnelly

On Mexico City: A Return to Rooms

It was several years ago now—on a trip to one of world’s densest cities—that I found myself thinking about rooms. Sometimes, ideas form less from a linear logic and more so from constellations: from disparate thoughts that web together into an unanticipated whole. It was in this wayward way, in the depths of Mexico City, that I found myself formulating a position on rooms.

Jonathon and I travelled to Mexico City intending to escape architecture. Yet, as anyone who has studied this field will know, studying architecture inherently changes the way you see the world. It imbues you with an inescapable attentiveness—to spatial gestures and filigree details that many people would simply skip by. Architecture inhabits you, as you do it, by seeping in under your skin. It is a consistent education.

This attentiveness began in our first tourist encounters. There were lessons in the broad public square, the Zócalo, a civic room where people gather to protest and perform. There was Frida Kahlo’s Casa Azul, where she painted until the day that she died, in spaces laced with relics and memory. Watching the film Roma, we saw rooms that spoke of class and gender, the very hierarchies we’re untangling to this day. Finally, there was the work of Luis Barragán, and the rooms he crafted throughout his career.

Luis Barragán is Mexico’s most famous modern architect. Born in 1902, in Guadalajara, he went on to study architecture and engineering before undertaking formative travels to Europe. He was a staunch Catholic whose exposure to Mexico’s unassuming vernacular buildings merged with his modernist education. The morphing of these influences, alongside a fascination with gardens, went on to underscore a remarkable body of work.

Much is written about Barragán’s work: there are sharply scripted analyses of his use of light, colour, and splendidly textured walls. And yet, instinctively, we were most drawn to the way he arranged his floor plans, primarily around rooms.

Perhaps this is because, as Louis Kahn once wrote, the room is where all architecture began.

The room is the most fundamental architectural formation; a primitive means of permanent enclosure defined by walls and openings. As Pier Vittorio Aureli writes: “If the purpose of architecture is to make space, then the room is the most direct form that responds to those intentions.” Their recognisable remnants have been uncovered within the ruins of the earliest recorded civilisations; their traces suggesting places of work, worship, and rest.

For much of my own architectural education, the room was a device to be sparingly used: after all, when activities can bleed into one another, why return to the functional strictness implied by rooms? While many buildings rely on rooms, the precedents that underpinned my studies focused on removing cellularity and, instead, separating spaces with lighter means, like columns and eroded walls. The aim was to suggest space rather than separate it; to imply distinction instead of drawing a firm line.

Within Australian architecture, the focus has long been on the open plan and its implied seamlessness: merging inside with outside, or living with dining. Perhaps this tendency is global; as the architect Stephen Bates notes: “It seems that not many people have been interested in rooms of late, because the Modern movement exploded the plan outward, and territory became blurred.”

And yet, in 2015, while visiting homes on the annual RIBA Awards tour, the British architect Mary Duggan termed the eloquent phrase ‘broken-plan homes’ to describe many of the projects they saw. There was a fundamental cultural shift towards enclosure, separation, and retreat as people sought inwardness and quiet. There was—in short—a return to rooms.

Emerging from my reading, and returning to Mexico City’s thrumming streets, my partner and I began to visit Barragán’s work.

We started at Casa Gilardi, on a tour led by the owner’s son. He spoke of a childhood chasing friends through yellow-tinted corridors, amidst bright pinks and brilliant blues. A few days later, we were ushered through Barragán’s Chapel of the Capuchinas by a small, rotund nun. She wordlessly pivoted each door open, revealing rooms that glowed like sunsets. Here was Barragán’s signature lyricism; his ode to his religious upbringing and his pursuit of his own holy trinity of mythology, beauty, and joy.

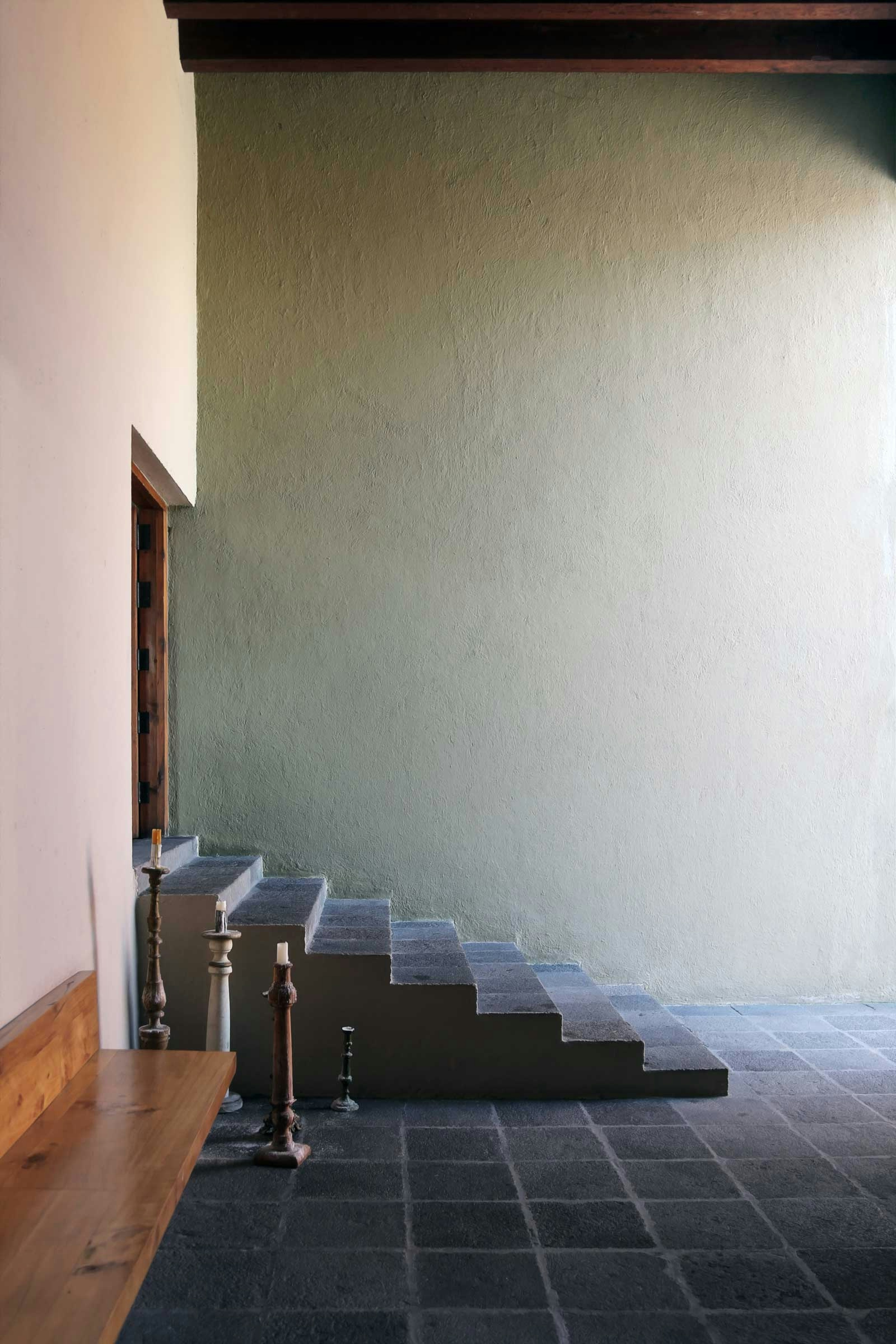

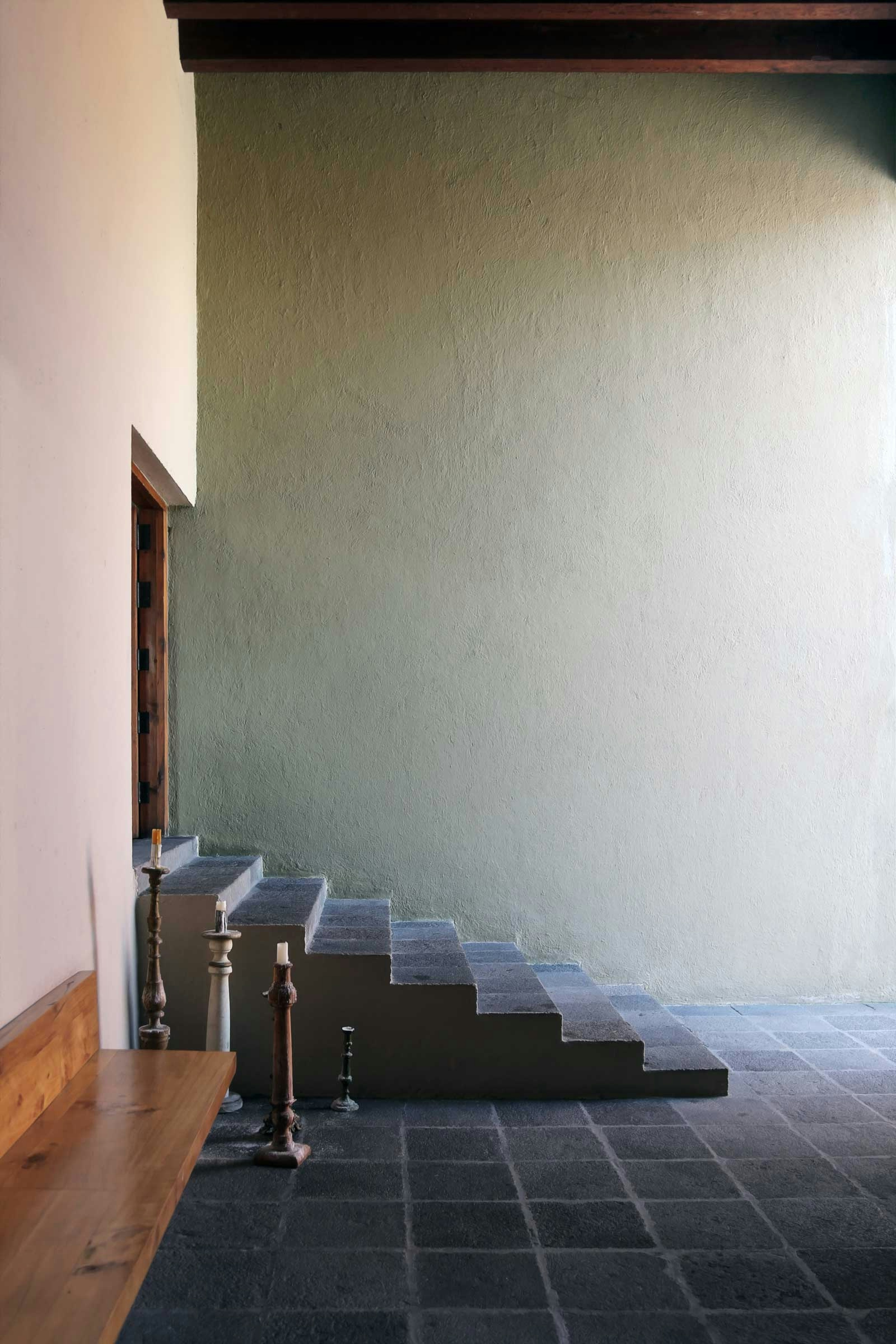

Later, we visited Barragan’s house and studio. We wove through a fragmented plan, moving through rooms both sparse and artfully cluttered, and emerging in courtyards that dripped with green. Then, on our last day, we visited Casa Pedregal, whose rooms felt generous and unencumbered, with space for life to unfold.

From afar, I’d never made sense of Barragan’s work. I’d viewed his homes like postcards: as perfect compositions of neatly coloured planes. His plans—with their endless successions of rooms and shifting levels—had always confused me. Yet, in person, they made complete sense.

Nothing prepared me for the profound beauty of Barragan’s architecture. His buildings meander up and down, revealing light and shadow in slow, thoughtful concert. The simplest devices—walls and proportion—hum in harmony. These rooms offer time and pause, privacy and possibility. These spaces—masterfully, magically—made space.

As I left Mexico City, I found myself pondering the connection between rooms and ‘room’—after all, linguistically, ‘room’ derives from ‘rum,’ a reference to space. This space is both physical—defined by walls and floors and roofs—and metaphysical. Think of time: how it can expand and give room for our thoughts; or space, which can be infinite or finite. All this, and much more, can be held within rooms.

I think Barragan intrinsically knew this. As he accepted his 1980 Pritzker Prize, architecture’s highest honour, he described an architecture of silence, solitude and serenity.

As architects, and as people, we make rooms to make room. We need spaces where we can stop, and feel welcomed, and close the door to the world beyond. We need to craft these spaces for others, and we need to carve them out for ourselves.

This, ultimately, is what our time in Mexico City, and our pilgrimage to Barragan’s work, offered me: an appreciation of the simple, unequivocal delight of spaces made great, and a pledge to return to rooms.

Field Notes

Written By:

Jennifer McMaster

Photos By:

Jonathon Donnelly